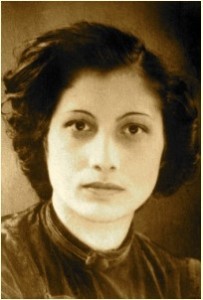

NOOR INAYAT KHAN was born in Moscow in the Vusoko Petrovsky monastery, a short distance from the Kremlin, on 1 January 1914. Her name meant “light of womanhood.” Her title was Pirzadi, daughter of the Pir. At home she was affectionately called Babuli. As the First World War engulfed Europe, the family left for England, where they lived for the next six years. In London, three more children were born. Noor, barely four years old, mothered them all.

NOOR INAYAT KHAN was born in Moscow in the Vusoko Petrovsky monastery, a short distance from the Kremlin, on 1 January 1914. Her name meant “light of womanhood.” Her title was Pirzadi, daughter of the Pir. At home she was affectionately called Babuli. As the First World War engulfed Europe, the family left for England, where they lived for the next six years. In London, three more children were born. Noor, barely four years old, mothered them all.

When Noor was six, the family set sail for France again and began to live in a large house on the outskirts of Paris. Hazrat Inayat Khan called the house Fazal Manzil – or ‘House of Blessing’ – and such a place it was. It became an idyllic home for the family, an open house full of music and meditation with Sufis visiting round the year.

The children played in the garden and loved sitting on the high steps outside the house looking out over the lights of Paris. They would dress up in their Indian clothes and give concerts before the Sufi guests. The four brothers and sisters formed a quartet.

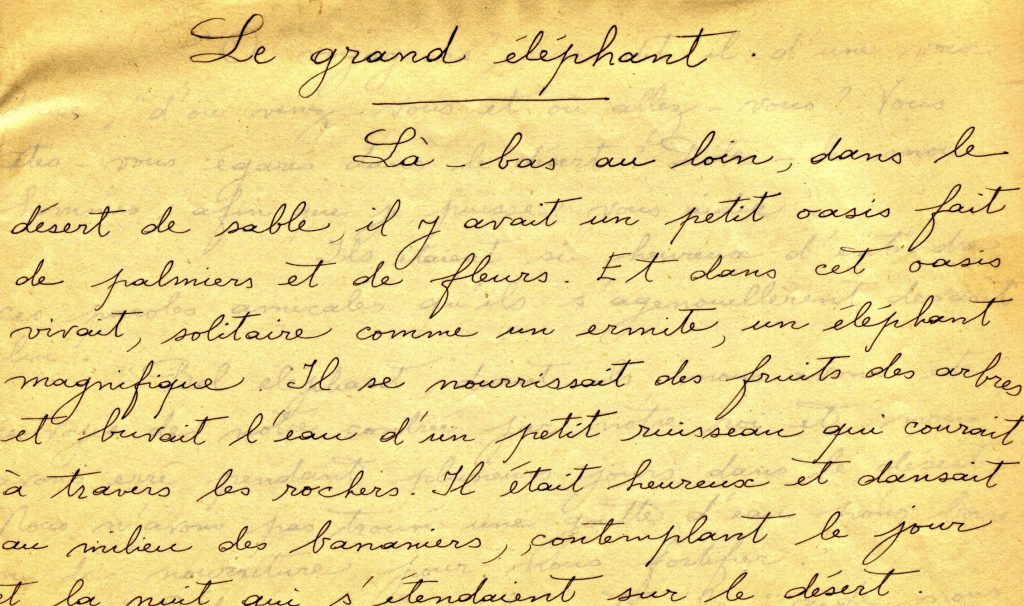

But in 1927, Hazrat Inayat Khan decided to return to India. He had not been keeping well lately and yearned to go back to his motherland. A few months later they received the devastating news of his death. Noor’s mother, Amina Begum, went into seclusion. Noor, at the tender age of thirteen, took responsibility for the family and became a mother to her siblings. She began to write poems and short stories and found solace in these when the burden of domestic chores became too much to bear.

After her schooling, Noor studied child psychology at the Sorbonne and also joined the École Normale to study music. Meanwhile, she was finding her feet as a writer of children’s stories. Her stories were published in the Sunday section of Le Figaro and in 1939 her first book, Twenty Jataka Tales, was published in England.

However war clouds were gathering in Europe and all dreams for the budding writer were quashed as England and France announced war against

Germany. In 1940 with the German army ready to enter Paris, Noor and Vilayat took a crucial decision that was to change their lives. Though they were Sufis and believed in nonviolence, they resolved to go to England and volunteer for the war effort.

In a bombed-out London, Vilayat volunteered for the Royal Air Force, and Noor volunteered for the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. There she was trained as a radio operator, joining the first batch of women to train in this field.

But while Noor was tapping away at her Morse code, she was being watched by the Special Operation Executive, who were looking out for people with language skills. The SOE was a crack organization set up by Churchill to aid the Resistance movements in Occupied countries. Their job was sabotage, and providing arms and money to the Resistance.

Noor was called for an interview at the offices of the SOE. She was told that she would be sent as an agent to occupied France after training. She would have no protection, as she would not be in uniform, and she would be shot if she was caught. Without a moment’s hesitation, she said she would take the job.

Noor was called for an interview at the offices of the SOE. She was told that she would be sent as an agent to occupied France after training. She would have no protection, as she would not be in uniform, and she would be shot if she was caught. Without a moment’s hesitation, she said she would take the job.

She was now to be trained as a secret agent. It was classic spy school; she was taught to handle guns, explosives, to break locks, to kill silently in the dark, to find sources, to use dead letter boxes and live letter boxes, to practice sending letters in code, and to improve her Morse code. Noor’s code name was Madeleine.

Finally the orders for her departure arrived. Armed only with a false passport, some French francs, her pistol and a set of four pills including the lethal cyanide pill, Noor prepared for her dangerous mission. On the moonlit night of June 16, she was flown covertly across the Channel. Back on French soil, she made her way alone to Paris and joined the circuit. It was the biggest SOE circuit in Europe, called Prosper. Soon Noor settled down and began transmission.

Within a week, disaster struck the Prosper circuit. All the top operatives were captured by the Gestapo and their wireless sets seized. Noor was advised to go into hiding immediately. Together with another SOE agent, she lay low, gathering information about betrayals and further arrests as the secret police closed in. Eventually London contacted her and asked her to return as it was too dangerous to stay on, but Noor refused, realizing that she was the last radio link left between London and Paris.

By mid-August Noor was the only British agent in Paris. Single-handedly she now started doing the work of six radio operators. The next three months, Noor was to survive in a dangerous cat and mouse game played by the Gestapo.

Sticking to the rules of her training, she frequently changed her position, kept her transmissions short, and even changed her appearance by constantly dyeing her hair. Noor’s communications helped London to pinpoint locations for arms drops, supply money and arms to the French Resistance and organize safe passages home for injured airmen. The Nazis knew about her and could even hear her transmissions but they could not catch her.

In London, her colleagues and seniors were stunned at her efficiency. Where most radio operators survived for six weeks, Noor had worked clandestinely for three months. Her messages were flawless and her code master felt a special sense of pride in her.

But the noose was tightening around Noor. Around the middle of October, she was still safe and would have managed to catch a flight out of France if she had not been betrayed. Noor’s address was sold to the Nazis for 100,000 francs. With this information the Gestapo arrested her and took her to their Headquarters at 84 Avenue Foch.

Noor immediately made an escape attempt, but was caught. A few weeks later she made another daring escape attempt with two other prisoners, loosening the sky window and clambering on the roof. If this escape had succeeded it would have gone down as one of the most daring escapes of the Second World War.

Noor was now labelled a “highly dangerous” prisoner, and became the first woman agent to be sent to a German prison. She was sent to Pforzheim prison on the edge of the Black Forest, where she stayed for a period of ten months.

stayed for a period of ten months.

Noor was kept in isolation, shackled in chains and foot irons. She could not feed or clean herself. She was regularly beaten, tortured and interrogated but she revealed nothing about her circuit and gave out no names.

On the night of September 11, Noor was ordered to come out of her cell. She was driven handcuffed to Karlsruhe and met three of her colleagues there. Together the women were driven to the railway station and made to board a train.

They reached Dachau at midnight and were led to the concentration camp. It was to be a long night for Noor. All night long, she was kicked and beaten and when her frail body had slumped on the floor, she was asked to kneel and shot point blank at the back of the head by an SS guard. Her last word was “Liberté.”

Back in England, both her mother and brother had the same dream. Noor came to them surrounded by blue light. She told them she was free.

On 16 January 1946, the French awarded Noor the Croix de Guerre, the highest civilian honour. Three years later in 1949, England awarded her the George Cross.

More than sixty-five years after the war, Noor’s story needs to be preserved for a new generation who need to know about the sacrifices made for freedom. Noor’s last word, “Liberté,” has been carved on a Memorial in Gordon Square to remind the world that a beautiful young woman unhesitatingly sacrificed her life, so the world could be free of Fascism.